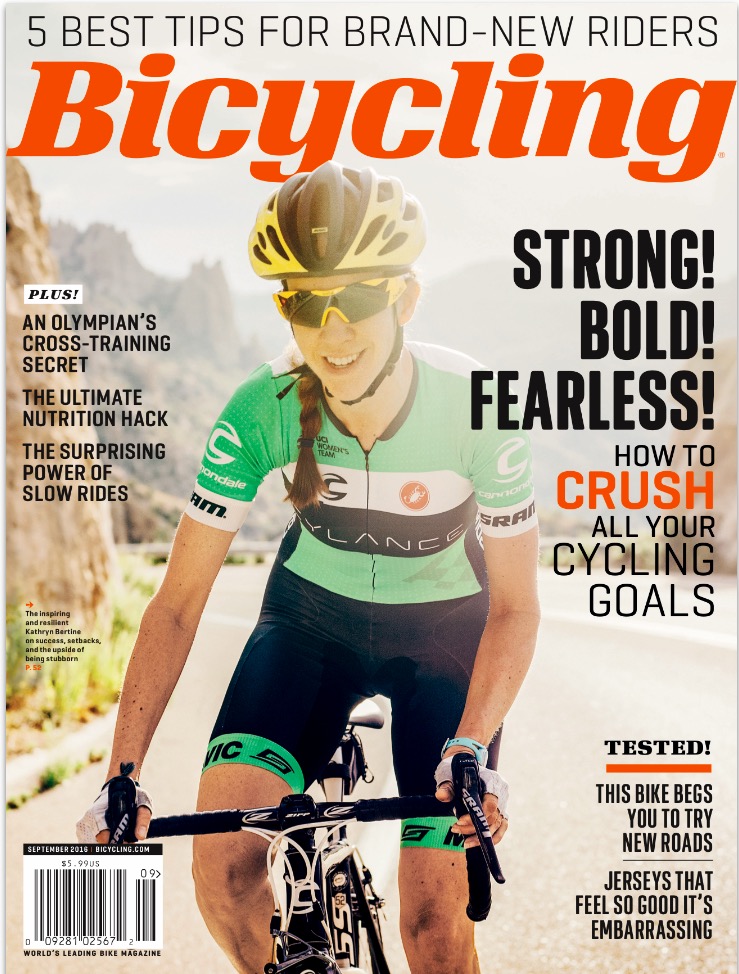

Athlete in several sports, writer, film-maker, activist, public speaker… Kathryn Bertine is a multifaceted woman who speaks with unparalleled eloquence about the sport she was part of for several years: professional cycling. Now she’s retired, but that doesn’t mean she’s not involved anymore. Very, very far from that. We caught up with her to discuss the current state of women’s cycling, the changes that have been done, the changes that need to be done, and her own experiences in her relentless journey towards equality.

Words and interview by Saul Miguel

Photos courtesy of Kathryn Bertine, unless credited

2018 was a particularly important year for the women’s side of our sport. There were more televised races than ever, and especially one of them, La Course by Le Tour de France – a race that Bertine herself, as a co-founder of Le Tour Entier, contributed to create five years ago – took the cycling world by storm by being arguably the most exciting pro cycling event of the season. It was also the first year for the Cyclists’ Alliance, a new organization that can be the key to positive change in women’s cycling, and the UCI, under the leadership of David Lappartient, announced some very important steps towards equality when it comes to salary and riders’ rights such as maternity leave.

However, there’s still a lot to be done. When Bertine started her career as a pro cyclist in 2007, she found a huge disparity when it comes to the conditions that women had to face compared to the women. Has it changed now? Yes and now, according to Bertine: «I think I can very confidently say that no, it hasn’t developed as much as it could. There are some positive changes being made right now, but we have to look at the history, the fact that the UCI has been around for 119 years, and only now we’re starting to see some change. I definitely applaud when change is being made, but it’s only being made because all the women that are standing up and speaking out about it. Had the previous leaders in the sport been smarter and wiser, then we would be a lot further along than we are now. So no, not enough has been done, but I’m hopeful», she states, adding this final hint of optimism.

One would think that we shouldn’t be speaking about this in 2019, but the reality is that we still have to do it. We need to do it. «It’s obvious it shouldn’t be like this, but I think that obviousness is at the same time part of the problem», she warns. «In our modern society, we make the assumption that everything out there is equal, because hey, it’s 2019. But the reality is that we’re shooting ourselves in the foot every time we assume that something is equal just because it’s modern times. That’s how the inequalities fall through the cracks, because people assume everything as equal, and it takes everybody standing up and making noise to even bring attention to the fact that things are not equal.»

As she quickly points out, this is far from being an exclusive problem in the small world on cycling, or even sport, but it happens in many other areas. «For example, I think it was only this past year when the women in Hollywood finally explained to people that they weren’t earning as much money as the men, and everybody said ‘What!? That’s crazy, it’s 2018!’ My solution to this is: every time we’re confronted with a situation that we think is equal, we have to ask: well, is it? And do a little bit of digging to find out. And if it’s not equal, then we need to call it out.»

Everyone can draw this conclussion: the day we stop thinking about it and taking action, it’s dead, and change won’t happen. It’s not enough until it’s truly equal. «Something I’ve noticed is that, if there’s a tiny bit of progress, it’s often expected that you should clap, when the question we should be asking is: And…? So if the UCI says: hey look, at this race we have equal prize money, then our response should be: that’s great that we have equal prize money at this particular race, so when is it going to be mandated at all races?»

The long and hard journey towards equality

Kathryn Bertine has a wealth of experience in her fight towards equality. So when we ask her if her list of disappointments and shockingly negative memories during this journey is a long one, she emphatically says: «Yes, absolutely!». It takes her a few seconds to mention a specific example, though. «I’m trying to pick something that is most relevant… I think the most shocking to me is what’s going on right now with ASO and the limited race for women at the Tour de France. That to me is shocking, that we went to ASO with a group, Le Tour Entier, in 2013, and we sat down at that meeting and we victoriously got the one day La Course for the next year. But our business plan and proposal was that if you start with one day it needs to be incrementally added so the next year will be three, and then five, and then seven, and then ten, fifteen, until it would be equal to the men. And what’s shocking to me is that at the time they say ‘Yes, yes, we will do this!’, and now they have not. The public is getting angrier and angrier that the women were not given the equality they were promised.»

Bertine elaborates on her comment: «So for me, what’s shocking is that ASO continues to do this and the fact that UCI is not taking measures to make that better. And related to this, it’s also shocking to me that so many managers and people who have been involved in the sport for a long time are actually calling out and saying ‘oh, this progress is happening too fast, it’s too quick’. That comes from a place of fear and laziness when people say that, rather than rushing up to the challenge and making it happen, that the women will be treated equally. So I’m a little bit shocked that so many people within the sport are still in a bubble, rather than looking at the bigger picture of what will happen and what can happen.» This is of course related to the news about the minimum wage announcement that the UCI published some months ago.

Her message gets more nuanced now: «The reforms by the UCI when it comes to the minimum wage are planned step by step. I rarely praise the UCI on anything [laughs] but the reality is that David Lappartient has structured the base salary growth from 2020 to 2023. He’s done that well, and I do appreciate that he’s taken that step. This way nobody should be complaining that this is happening too fast. It should already been in place and happening. If managers are afraid that they might be losing sponsors they need to find new sponsors who believe that women should be paid equally. And if they can’t do that, then they need to leave the sport.»

David Lappartient

Since he was elected as the new UCI president in September 2017, David Lappartient has been very vocal about his desire to have a women’s Tour de France and also a Paris-Roubaix, trying to pressure ASO, the organizer of both events, to do more for the women in sport. The long expected plans to establish a minumum wage for the women have also happened under his leadership. «I’ve been in communication with him this past year. He’s aware of my focus and my need to see change happening in women’s cycling, and I’m aware that he’s making some great progress in terms of the base salary», she tells us with cautious praise, before continuing: «Now, when it comes to anybody in a position of leadership, and especially for talking about a president of any organization, then it’s important that we remember always that talk and action are different things. It’s very easy to tell someone ‘I’m very supportive of what you’re saying’ and tell everyone what they want to hear. He states he wants to see a women’s Tour de France of minimum 10 days and more men’s races having a women’s equivalent. I’m very supportive of what he’s saying. However, talk without action equals shit, so what we need to do is make talk turn into action.»

We’ll all probably agree on that. How does Bertine personally feel about it, though? Will Lappartient deliver? «We need to hold David Lappartient accountable that, just because he wants to see women’s cycling have more opportunities, that’s great, but now he needs to step up and make that happen. We don’t want people in leadership think that just talking is enough – it’s time to do action. I do believe that Lappartient is capable of creating action, but we need to see it now.»

Considering the reforms and announcements made so far during his leadership, there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic. But we’ll have to leave that to the reader. Eventually, time will tell.

The Cyclists’ Alliance and why it makes a difference

The Cyclists’ Alliance was launched in late 2017 by former riders Iris Slappendel and Carmen Small, along with active rider Gracie Elvin (Mitchelton-Scott). With the mission of representing the competitive, economic and personal interests of all professional women cyclists, the birth of the Alliance was received with massive enthusiasm and optimism. Rightfully so, we must add.

Having been in close contact with the Alliance since its beginnigs, Bertine tells CiclismoFem her views on what’s the best approach for such an organization. «The best tactic to make change done is to divide and conquer. If the Cyclists’ Alliance is focusing on some specific aspects of women’s cycling, like making sure that riders have a proper contract, that more race opportunities are possible, then those are great, but I encourage every alliance to try not to tackle every problem but instead of that divide and conquer, and what I mean with that is support and encourage other groups to take one specific aspect of change in the sport.»

She puts some examples to illustrate her idea: «Can you image how beneficial it would be if we had like five different cycling alliances and one of them was tackling the gender pay gap, the other one was tackling equal opportunities to race, the other one was tackling equal pay at every race…? The best way for every organization is to select one or two topics and get those done, and then move on to incorporate what comes next», and then adds a more specific one: «This is why, for example, we at Le Tour Entier went specifically after the Tour de France, because we know that is the one race the entire world knows about, whether they’re cyclists or not. Change has to start from the top down, so we went after that one thing. But the good thing is that the ripple effect it created was fantastic: the Madrid Challenge was created and other races started opening their eyes.»

In any case, Kathryn makes it clear that she’s 100% supportive of what the Cyclists’ Alliance is doing. «It’s definitely a fantastic creation. I’m colleagues with these wonderful women and I fully support the initiative of what they’re standing up for», she states, before adding an important remark: «I also do think that change has to come from within the sport, and that’s precisely how riders like Iris, Carmen, Gracie, who are the visible faces of the organization, are doing a great job. This alliance is also very beneficial because it’s not the women’s affiliate commission of the UCI. Every time there’s an affiliate commission within an organization that is already corrupt, then we’re not going to see any big change being made, because the group is controlled by the bigger organization. What’s great about the Cyclist’s Alliance is that they’re outside of that controlled group, and now we can put more pressure on certain parts. We’re seeing bigger changes because people outside the UCI are making a difference.»

Tour de France: the ultimate goal for the women’s calendar?

One of the most frequent discussions related to the creation of a women’s Tour de France is whether the women would be able or not to cope with a three week long race. Actually, spending time in such a discussion is plain wrong. It has already been proven both in theory and practice. «We actually talked a lot about this in the film ‘Half the Road’. It’s not only inaccurate to say that women can’t ride the same distances as the men, but we actually have the science, physiologists explaining that it’s not just a matter of saying that ‘oh, the women can do anything’, but physiologically it’s been proven, not only in cycling but in all female athletes, that women have an advantage over the men when it comes to endurance. It’s been proven, for example, in endurance running events. When events get longer, women get comparatively stronger, and they narrow the time gap to the men. Not to the point to be able to compete against the men, but the thing is that women can absolutely do what men do, if not better in relative terms.»

In cycling, we have a recent example with what Evelyn Stevens and Trixi Worrack did in 2014. Both rode the Giro Rosa (10 stages) and went to Germany right after the Italian race finished, without a single rest day, to ride the Thüringen Rundfahrt (7 stages). That made 17 days of racing in a row, plus a long transfer in between. And the most impressive thing is that Stevens actually won the second race against a strong field of fresh riders. Worrack also had a comparatively better performance in the second race.

Bertine quickly mentions that this is not even new and there are more similar examples. «It’s interesting to note that it’s not only did Evelyn Stevens and Trixi Worrack prove this, but it’s already been proven in the 60’s and in the 80’s, when women did take part in the Tour de France. In this modern day and age it’s so easy to use social media, to use the internet to find the answers of what one is looking for, so we have to educate the people who think that women aren’t physically capable and we have to say that’s ridiculous and that we’ve proved that for decades – it’s not a new thing.»

It’s time to leave that argument behind. But how would Kathryn Bertine herself design a Tour de France for women, provided she had the resources to do it? Let’s put ourselves in an idealistic mood for a while.

«I’d create a Tour de France that was perfectly equal to the men. However, I would ensure that the growth happened incrementally so the women’s teams had the chance to include that race within their budget and plans, which is of course what we tried to plan with ASO five years ago, almost six already.» She obviously has a very clear idea about this because she had already planned it long ago.

She continues with her plan: «If I had to start now, for this upcoming edition I’d have a five day Tour de France, and then in 2020 it would go up to ten days. Now, between 2020 and 2025 it would incrementally build up two or three days per year until it’s fully equal. I’d give the sport roughly five years to reach that goal of full equality at the Tour de France. The problem is, it could be here right now. We’re already five years late as ASO hasn’t made it grow since La Course started. So a part of me thinks ‘let’s make it three weeks right now!’ because it should already be three weeks. But if I had to start from scratch, I’d create that plan of full equality in five years, going step by step.»

Who wouldn’t like such a race? Not so fast. Apparently, not even all people inside the sport are keen on the idea. Bertine respects that reasoning, but doesn’t share it at all. «You’ll hear some women from the peloton say: ‘I don’t want to do a three weeks race’. But what we have to remember is that not every rider is an endurance rider, not every rider wants to race three weeks. Some of them are much happier doing one day races, just like I don’t have any desire to ride track cycling events [laughs], but I’d never say that there shouldn’t be track competitions just because I’m not good at them or they don’t suit me. So, if some don’t want to do a Tour de France, that’s okay, but there are so many women who do, so you need to be supportive of those who are able and willing of doing the Tour de France.»

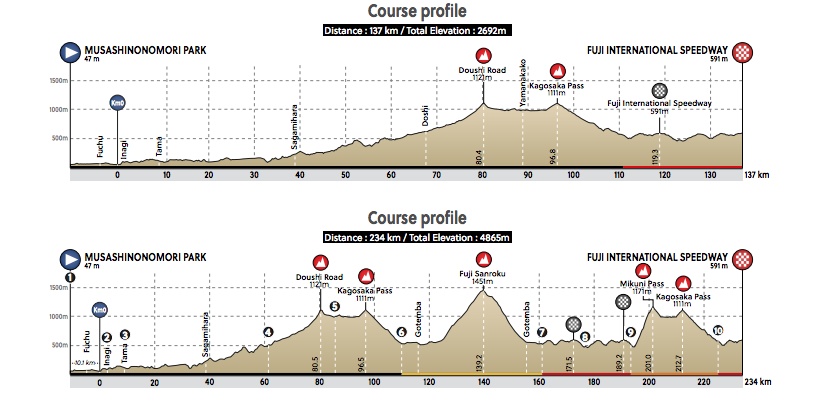

Are watered down courses acceptable?

When we mention the divisive debate and the mixed reactions that followed the announcement of the road courses for the Tokyo Olympics, Bertine exposes a similar view. It’s maybe a human condition to defend what is more favourable for the individual, instead of trying to see the bigger picture and what’s the greater good in the end. She also understands that reaction, but believes it’s a wrong approach. «It makes sense to me if a sprinter is looking at the Tokyo course and thinking: ‘Oh, awesome, that’s a good course for me’. I can understand that. And if a climber is looking at this and says: ‘Hey, how come we don’t have the same mountains at the men, that would’ve been better for me’. It’s one of these cases in which we have to realize that different courses suit different athletes.»

«But what I’ve seen, and I’ve been to UCI World Championships eight times during my career… what it’s amazing about all of these courses is that they try to include everything, so there will be climbs, flat sections, technical areas, and that’s what would make the ideal course for the ideal athlete – somebody who can be proficient in a multifaceted course. So the Olympics, too, should embrace the same philosophy, and definitely not water anything down for women, but also create such a course which is going to show which riders have that multifaceted expertise or all-around abilities.»

No doubt it’s a tricky subject, for Kathryn somehow tends to speak slower now, as if she was trying to carefully choose the right words to put it. «So yeah, maybe some women aren’t speaking out about Tokyo simply because they prefer the way it is, and I can understand that, but at the same time they should speak out about the fact that this is a course that it’s been watered down and it’s different from the men’s. So they need to grow up a little bit and embrace that philosophy that doesn’t matter if the race suits you or not, it’s been watered down from the men’s version because people think women aren’t capable.»

Bertine stands firmly against watered down races. «I have a real problem with the Olympic course in Tokyo, on two levels. One, because of the fact that the women’s race is indeed a watered down version of the men’s course. That’s just wrong. It needs to be equal. Looks at just every other Olympic event – they’re held on the same course, or place, or pool, whatever it is. Look at marathon, an endurance event: same course for men and women. Or even within cycling, with mountain bike: the race is held in the same circuit for both.»

But how did this happen? Now comes her biggest concern, and something that would indeed be a sign of institutional bias and inequality. «Here’s what’s most alarming to me: how did this happen for an Olympic event? Because now we have different factors at play. I’m not sure if this is something to investigate, but between the UCI, the race directors, and the IOC [International Olympic Committee], who prides themselves on being equal, clearly something got approved and something got ‘okayed’ that yes, this is acceptable for women. So, did the IOC not know what was going on, or did they know? Either way, it’s not acceptable that this is happening, that there is this glaring inconsistency in cycling.»

«And this adds one more thing to that pile of things that women need to speak up about and change. It’s another thing we have to do just to be considered equal, and it’s truly exhausting, that we have to put energy into fighting something like this, that the women’s course is different to the men’s.» Bertine stops for a moment to think of a way to fix this, but the solution doesn’t look easy: «But we have one year and a half until the race is happening. There’s enough time to make this change, but my biggest fear is that it will go left unchallenged, because it’s going to take somebody to put the pressure on UCI and IOC to make that change happen, and the women are also busy racing, doing their jobs as pro cyclists, so if they have to take this too, it’s not okay, it’s not right.»

The ASO paradox

Clearly, ASO hasn’t taken advantage of the momentum created when La Course was born. Five years later it’s still a one day race. Is it then a mistake to keep trying when ASO is so obviously not willing to create more opportunities for the female pro cyclists? Wouldn’t it be wiser to support and rely on other organizations that are more supportive for the women’s sport?

Bertine still thinks that putting the pressure on ASO to make the change is the way to go. «I still stand firm that ASO needs to create this change, because at the moment they have the race that is the pinnacle of the sport, which is the Tour de France. Yes, absolutely, we should sync our efforts into supporting or creating other organizations similar to ASO which will focus properly on women, and that would be great, as long as that would lead to the arrival of a Tour de France-like race in terms of media exposure and social awareness. If someone can create something that it’s just equal to ASO’s product, then it’s fantastic. But the way I think is most effective is to get the organization that is currently in power to realize that creating the race for the women is not only morally the right thing to do but also financially the right thing to do, because they’re going to get benefit from this. If someone else wants and is able to create something just as equal, that’s fine, but I think it’s a better battle to work with the one in power, and to create change together.»

Let’s be honest, it’s very unlikely that any other organizer could come up with any other race just as iconic as the Tour de France. The Tour is just too big. It’s iconic, it’s got a big history, it instantly evokes images. You can’t replicate that. «I believe that we should honor the fact that history matters. The Tour has been around for more than a century and that’s very important. It’s a wonderful history that they have. The problem is that they’re not bringing it up to a place in modernity and, if we can win that battle and the women are included equally… You know, I want to see ASO thrive. I want to see the Tour de France thrive, because history is so important, but now we need women to be part of that history too.»

If done right, the positive domino effect of a women’s Tour de France shouldn’t be ignored, too. That exposure could potentially bring many new fans and sponsors. That way, other races and the sport as a whole would benefit from that.

Everything counts

When it comes to giving women’s cycling the visibility it deserves, there are so many factors to consider. The role of journalists and fans on this cannot be understated. But there’s something that may be even more effective: the support of their male equivalents. There are not many examples, but Mark Cavendish has expressed multiple times on social media his appreciation for women’s cycling and his conviction than the way they ride is even more exciting than the men.

Bertine has some other examples. «Another helpful, supportive rider is the retired US pro cyclists Phil Gaimon. He’s also a friend of mine and he’s very, very supportive. He’s been great and he does this not just for me because we’re friends, but for other female pro athletes – he does speak very highly and positively about them. The same goes for another recently retired rider: Brad Huff of Rally Cycling. These guys have not just spoken these words but shared their support for women on a public stage. And that’s what we need, we need guys like these, like Phil and Brad and Mark. We need more of the men to stand up for the women in sport, to be fans of us just as much as we are fans of them, to be our professional colleagues.»

She elaborates on why that support matters: «That would move the entire sport forward. I would like to see more or that. I think that often, on the men’s side of the sport, they are very self-focused about their own jobs and jobs as athletes, but if they can share and give a little bit of exposure to our side, then all of cycling will move forward. So the more fans we bring in to cycling, the better, and these new fans will follow both the men and the women.»

Past and future

As a former rider with many years of experience in the peloton, but also being someone who didn’t start with cycling as a very young age, it’s interesting to hear Bertine’s first impressions inside this sport, and how she found some unexpected challenges. «When I first started cycling I had a coach for learning the best tactics in terms of training, but what I didn’t have a very good knowledge of was the technical side of the sport, so for example I thought that every cassette of every bike we had was the same, that everyone had the same cassette, and I didn’t know that you can change that for something easier, or harder. And I didn’t learn that for three years.»

It’s a good opportunity for practising the very healthy habit of making a bit of fun of oneself, and Kathryn takes full advantage of it: «That sounds like a little bit of a comedy [laughs]. When someone asked me: what are you riding on? I just thought: same wheel that everyone rides on! It really became an education for me to understand the technical side of the sport, because sometimes coaches would assume that you already know something, and they don’t bother with the small details that for me were a very big thing.»

However, she wouldn’t change a lot if she had the opportunity to go back in time and start again. «In terms of the larger picture, don’t think I’d change too much about my journey in cycling, because everything I went through brought me to where I am right now, and I think I needed to go on that path to truly realize how much work needed to be done in cycling. No regrets! Even about the worst stuff I still say no regrets. As long as you learn from something, there’s nothing to regret.»

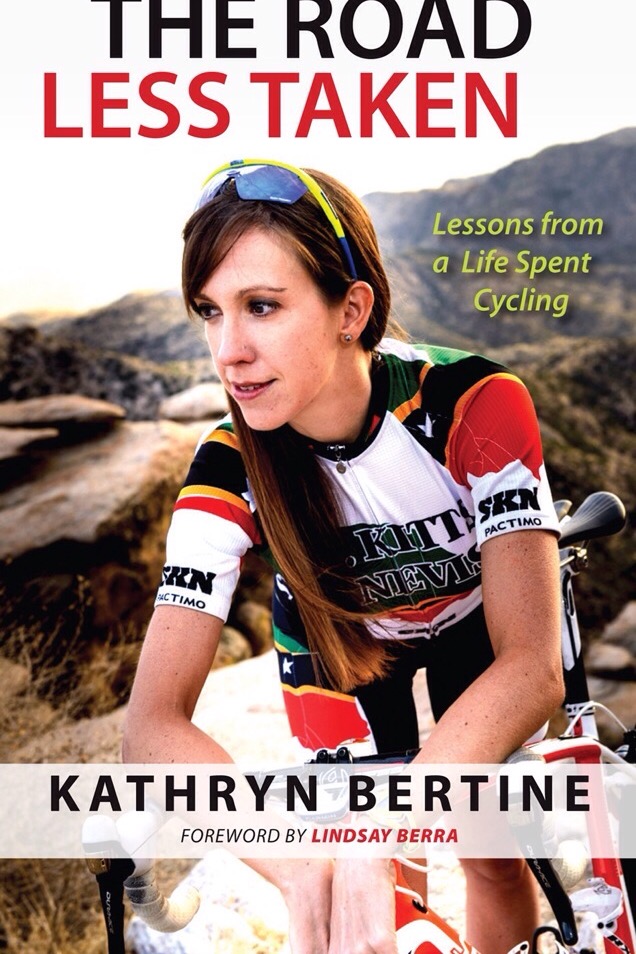

Kathryn Bertine is not a pro cyclist anymore, but that doesn’s stop her from keeping herself busy with several projects. «Currently I’m working on my next book, which will be about the journey through both the inequality and triumph that we’ve experience in cycling, and especially about how we’re all capable of creating change. Because if I can, then anyone can. I’m working on this book right now, but I hope to get back to work on a documentary film again in the future. I’m also currently running a Homestretch Foundation here in Tucson, to help female athletes who are struggling with gender pay gap.»

Maybe a second part of ‘Half the Road’? «There’s no doubt there will be another documentary film in the future, but now I’m busy with my next book. That’s what’s going on at the moment, keeping me busy [laughs].»

Creating change and making a difference, that’s what gives her a sense of success. There’s a sense of honest, genuine modesty when she explains how she accomplishes her goals. «I always feel very uncomfortable talking about myself under the question ‘do I feel I’ve made a difference?’ It feels weird for me to say that. I do feel I’ve helped create a difference but here’s the key: if I helped it’s because I brought other voices along. I didn’t make this alone. It’s not a solo mission, it’s because others have come with me, and so together [emphasizes this word] we are making a difference. If I have inspired others to stand out and thrive, that gives me a lot of joy and it’s a real measure of success.»

Perhaps, making others realize that they can also make a difference themselves is indeed the most important contribution, and something bigger than the individual change one can make.